Rumination in Interpersonal Conflict: Why It Happens and How to Stop the Cycle

What Is Rumination?

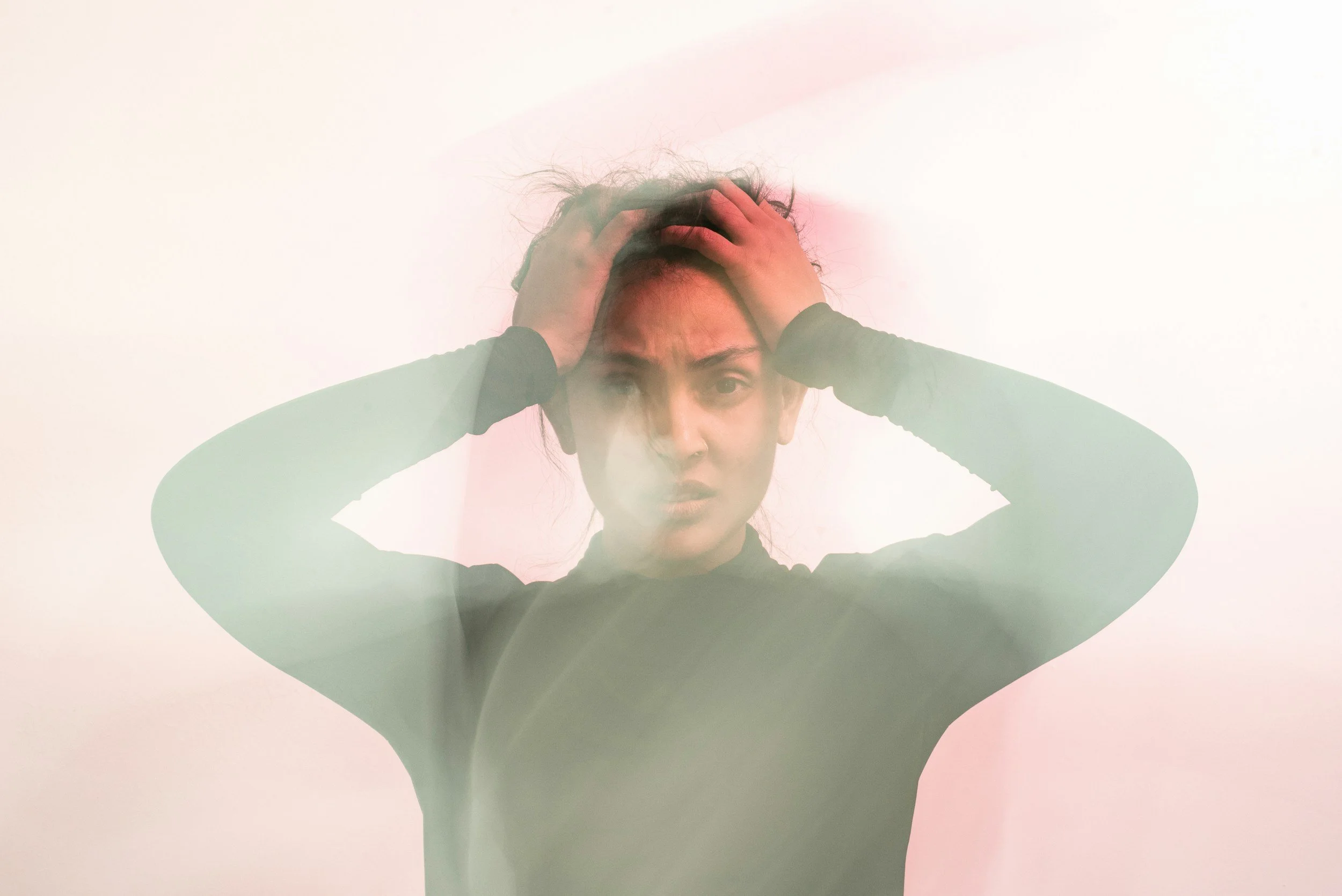

Rumination is repetitive, circular thinking about a problem, concern, or distressing situation without moving toward resolution. It often occurs after interpersonal conflict, perceived rejection, or uncertainty in relationships.

When something feels emotionally threatening, the brain naturally tries to make sense of it through analysis. While reflection can sometimes be useful, rumination keeps the mind stuck in loops of distress, reinforcing negative emotions rather than leading to clarity or action.

Common Forms of Rumination During Interpersonal Conflict

Rumination related to relationships often includes:

Replaying conversations or interactions repeatedly

Analyzing what the other person might be thinking or feeling about you

Creating negative narratives about the other person's intentions or character

Mentally rehearsing confrontations or conversations that may never happen

Comparing yourself to others or questioning your worth

Searching for evidence that confirms your fears or negative interpretations

These patterns can feel urgent and difficult to interrupt, especially when we are feeling intense and difficult emotions.

Why Rumination Persists

Rumination continues because it serves short-term psychological functions:

It creates the illusion of problem-solving or control

It reduces uncertainty, even when conclusions are painful

It feels like emotional preparation or self-protection

It is reinforced by occasional insights or realizations

Attempts to suppress thoughts often make them stronger

Over time, this cycle can increase emotional exhaustion and intensify anxiety or low mood.

Evidence-Based Strategies to Reduce Rumination

After interpersonal conflict, it’s common for the mind to replay conversations and search for certainty or closure. These strategies focus on interrupting that mental loop rather than trying to resolve it through more thinking.

Cognitive restructuring / Cognitive reappraisal: Question the story your mind is telling. Ask whether your thoughts are facts or interpretations, and look for more balanced explanations.

Mindfulness / Decentering: Practice noticing rumination thoughts without engaging them. When a thought repeats, acknowledge it and gently return your attention to the present moment.

Attention training/Postponement of worry/rumination: Recognize rumination or worry as a habit, not problem-solving. When you catch yourself looping, deliberately shift attention to something concrete or meaningful.

Behavioral activation / Values-based action: Stay behaviorally engaged. Continue with daily activities or values-based actions, even if your mind wants to withdraw and replay the conflict.

Acceptance / Distress tolerance: Allow discomfort without trying to fix it. Let thoughts and feelings be present without arguing with them—this often reduces their intensity over time.

Assertiveness training / Interpersonal effectiveness: Use assertiveness to reduce unresolved conflict. Assertiveness does not stop rumination once it starts, but it can reduce how often it occurs. Clearly expressing needs, boundaries, or concerns in the moment can prevent conflicts from remaining unresolved and replaying later. When people feel they have said what needed to be said, they are less likely to ruminate afterward.

When Additional Support May Help

If rumination is significantly interfering with daily functioning, disrupting sleep or appetite, increasing isolation, or contributing to worsening anxiety or depression, professional support may be helpful. Therapy can provide a supportive space to explore these patterns and develop personalized tools for managing them.

A Compassionate Reminder

The goal is not to eliminate ruminative thoughts entirely. The mind naturally produces them, especially in moments of relational pain. The aim is to change your relationship with these thoughts — to notice them, unhook from them, and gently redirect your energy toward what matters most.

With practice and support, it is possible to step out of the cycle of rumination and move forward with greater clarity and self-compassion.

References

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. G. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice (pp. 77–108). Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Martell, C. R., Dimidjian, S., & Herman-Dunn, R. (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide. Guilford Press.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(5), 400–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x

Normann, N., & Morina, N. (2018). The efficacy of metacognitive therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2211. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02211

Segal, Z. V., Williams, J. M. G., & Teasdale, J. D. (2013). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Watkins, E. R. (2008). Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 163–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.2.163

Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Guilford Press.

Wells, A., & Matthews, G. (1994). Attention and emotion: A clinical perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Disclaimer

This article is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional mental health assessment, diagnosis, or treatment. The strategies described are evidence-based but may not be appropriate for everyone or every situation.

Reading or applying the information in this article does not establish a therapeutic relationship. If you are experiencing significant distress, persistent rumination, or symptoms that interfere with daily functioning, you are encouraged to consult a qualified mental health professional. In cases of crisis or immediate risk, seek emergency services or local crisis support.